The United States (US) healthcare system is a grotesque and ancient monster made of fragmented yet codependent parts. Some pieces are attached purposefully to the frame, intentionally welded in place, and many others are haphazardly stuck on like chewing gum to the sole of a shoe. It is impossible to comprehend this behemoth monstrosity in one glance or from one angle. It certainly cannot be explained in one blog post. I’m not sure we can fully appreciate this misshapen colossus in a dozen posts. But complexity is not an excuse for apathy! Onward!

What’s the deal with the U.S. health system?

Nearly all actors in the US health system are treated primarily as business firms. Healthcare is not treated as a public good or regulated like a public utility. It is bought and sold, in a rather complicated fashion. While I, like many people, find this approach to be a very bad one in terms of promoting health equity and effectively managing our collective resources, this is the reality of the situation. In order to fix this monstrous system, we must understand it, and to understand it, we must delve at least a little ways into health economics

I know, I know. Economics is SO boring. It’s why many of us leave it to Janet Yellen (she seems smart) or a bunch of Harvard MBAs (they sure think they’re smart). But economics is a social science and it depends on what we think and do and value. If we completely outsource our economic understanding to others, then we will not have economics that thinks and acts and values what we do.

Janet Yellen is an economist and served as the US Secretary of the Treasury. The dude is finance bro clipart.

Economics 101

There are two famous economic axioms (or fundamental accepted truths).

- There is no such thing as a free lunch.

- People respond to incentives.

These are true. They are also too simple to fully explain the range of human behavior that we observe in the world. Still, they remain axioms for a reason and a good place to start.

Lunchtime. Economists say this thing about lunch because in economics, nothing is free. Everything costs something to someone. Perhaps it doesn’t cost you money, but maybe it costs you time or energy, and at the very least it comes at the expense of what you could have been doing instead. When those timeshare salesmen offer you free breakfast, you know that breakfast ain’t free. There’s no such thing as a free lunch.

The accompanying assumption is that no one will give you lunch for free. Ostensibly, we won’t provide or do anything if it doesn’t benefit us in some way. This tinges all of our interactions with a bit of suspicion, doesn’t it? As you look down at your dry blueberry muffin, you may question the motivations of the man in a Hawaiian shirt with gelled hair who “wants to get you the best deal.” What are you getting out of this? Am I missing something?

In general and on average, these assumptions hold. People tend to do the things that benefit them. Oftentimes that means making some money. Other times we’re not making much money, but we really believe in the cause or are devoted to a certain principle. Maybe we aren’t making any money, but instead feel a sense of personal satisfaction or happiness when helping someone. These things and feelings have value. Economists sometimes even try to quantify them in dollars. This doesn’t prove the axiom false, it just softens the suspicions that swirl around it when we interact with each other. (But maybe not with that timeshare salesman.)

Sam Cooke knows that the best things in life are free, like the moon, the stars, and robins that sing. Timeshares are not free.

Make me. On the first day of my freshman introductory economics course in college, the professor quietly entered the room, set his leather bag down on the table, and pulled out a small white envelope full of money. Gazing at the room of a hundred-some-odd 18 year old kids, he silently began to toss the money onto the floor. First, it was a penny. No one moved. Then, a nickel, followed by a dime. We watched, we stirred, but no one rose from their seats. Then a quarter clinked onto the shiny linoleum and a girl in the front row cautiously stood and picked it up. Low effort. The subsequent dollar bill fluttering to the ground inspired a few others in the front row to go pick it up. The fervor increased with the $5 and $10 bills. By the time a wrinkled green Andrew Jackson floated to the floor, boys from the back row were rushing up to snatch it.

What was happening here? First, it was a valiant attempt by one of my favorite professors to make economics less boring. Second, it was a simple demonstration of our second axiom: people respond to incentives. The more money on the floor, the harder the class worked, in general, on average, to go get it. However, most of the students, myself included, didn’t try to take the money at all. We saw the $20 bill but didn’t make a move. What else was happening in the room? It was the first day of class, no one knew what was expected or what rules there were. Most of us decided that $20 wasn’t enough to risk punishment or embarrassment. Many of us were also in the middle of a row or the back of the classroom, and it would have required a substantial effort to climb over strangers and push past new classmates. What if we looked crazy? Or greedy? Or uncool? People do respond to incentives, but they do not respond ONLY to incentives.

Everything can be blamed on misaligned incentives

Incentives are misaligned when people are inspired to act in a way that does not result in the desired goal. This can occur when there are conflicts in the desired goals or when there are unintended consequences to policies or rules.

The healthcare system is rife with conflicting goals. A surgeon who is paid for each knee replacement they perform will likely do more knee replacements, even if we want them to only perform knee replacements for patients who would truly benefit from the surgery. Conversely, a surgeon who is paid a salary no matter how many knee replacements they perform will likely perform as few surgeries as possible to minimize their work, even if we want them to perform beneficial surgeries for as many patients as possible.

Our healthcare monster also routinely steps in gum. Whenever we try to make a small policy change, we set off a cascade of unintended consequences, which we try to solve with more patchwork policies, regulations, and programs. The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) was passed in 1986. This required all Medicare participating hospitals to provide appropriate medical screening for emergency conditions and stabilize patients, regardless of their ability to pay. This increased visits to the emergency department, as care was now mandatory even if a patient couldn’t pay. This is good news! Now no one is being left on a stretcher to die and even poor people can get necessary emergency care.

However, there was no new funding for this law, which meant that hospitals were footing the bill for all of these new visits for great emergency care. Hospitals didn’t like paying for free lunch, so they started closing their emergency departments to focus on other aspects of care. Not good news!

Everything can NOT be blamed on misaligned incentives

Part of the reason we haven’t achieved durable health reform in the US is because we can’t agree on what we want our system to do. It’s hard to evaluate whether or not incentives are aligned in a system if you don’t know what it’s supposed to be doing!

So what do we want? Is the goal for patients to get any care that they want at any time regardless of need or value? Is it to have providers make as much money as possible? Or for the insurance companies to make as much money as possible? Is it to maximize “freedom” in the system? Freedom from who or what? Or freedom to do what? Is our goal to minimize total resource utilization? Whose resources? Is it to have the best system in the world? Best in the world at what?

Okay, enough of the boring economics, WHAT is the DEAL with the US Health System???

Right now, the system only reliably and clearly achieves one thing: providing very expensive care for people with money. This is because we rely on a system of profit-seeking firms to deliver healthcare as a service to customers but without any of the typical mechanisms that reduce cost and increase quality in a “free market.”

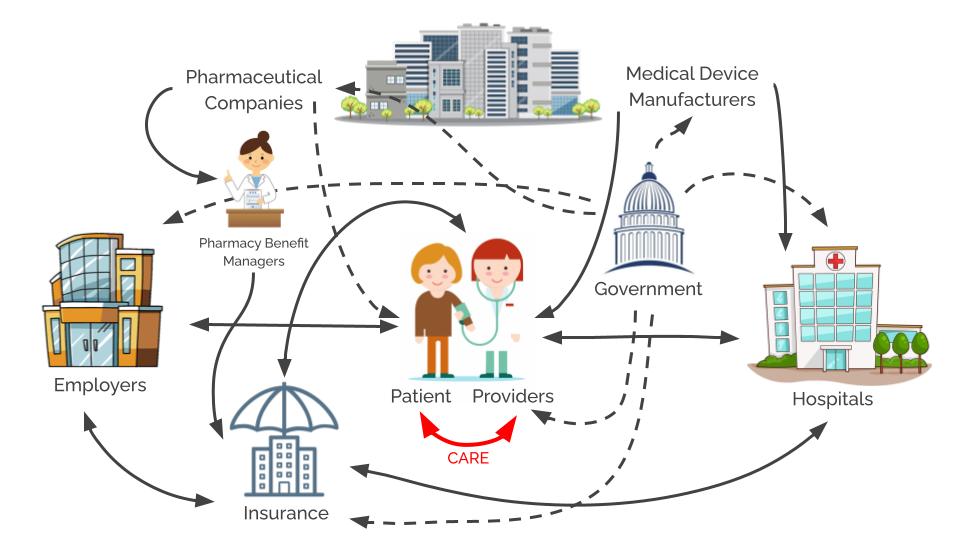

The US health system is NOT a “free market” and our incentives are NOT aligned. Patients try to seek care from complex systems and those systems churn and hum and buzz behind the scenes, catering to almost every other agent in the system besides the patient. When the machine has finished its business, it spits out a complicated bill 10 months later.

I believe that relying solely on business principles to manage the healthcare system is not only an inefficient way to achieve population health goals, but antithetical to a commitment to justice. Still, any healthcare system will have to interact with numerous sectors of the economy, all of which are guided by business principles and business ethics. Ignoring these realities is impractical and ineffective.

Phew. This is complicated. I promise that you do not want me to try to explain all of these arrows all at once. We’re going to take it piece by piece.

Introducing the Bad Guy Series

The complexity of this mess can make our eyes glaze over and have us looking for the nearest weighted blanket and someone to blame. It is not hard to find a bad guy in this system. All of the parts play a role in upholding our misery.

When there are bad guys everywhere, I tend to point my finger at the system. I like to focus more on the connecting lines in diagrams and less on the points where they end. But this blame is also incomplete. System level change is rarely accomplished by individuals but change is never accomplished without them. Focusing on the social structures and environments helps us work together, but acknowledging the role of individual actors helps us to know what work to do.

I’m going to take us through the situation of each of these major players. We’ll unpack their corner of the crazy diagram above and look at how they contribute to the dysfunction. I’ll try to explain why they’re doing what they’re doing, what they might be achieving for us, and how I think these individual actors should be better.

The lineup:

- pharmaceutical companies

- health insurers and pharmacy benefit managers

- hospitals

- medical device manufacturers

- patients and employers

- physicians

- the government

Stay tuned for more. I’ll link to the finished blog posts above as I finish them.

Truly glad to have writing such as this in my email today. Thankfully I was able to sort past all of the other emails offering “Free” incentives to find something that was worth the time spent. You have a wonderful gift – thank you for taking the time to share it. Now go run for office!

LikeLike

Can’t wait for the next one!!Sent from my iPhone

LikeLike