Every day, I work for the care and preservation of life. Every day, I see different lives, different suffering, different joy. Every day, I care for vulnerable people.

A lot of my patients have cancer. We have to stare mortality in the face together and they have to figure out what life means to them. A lot of their choices are made more difficult by the technological advances we’ve created to preserve the flesh. Do I want that tube or this debilitating treatment or that awful medicine or that other tube? For what purpose? At what cost? Will it prolong my life or just sustain my body? More importantly, will it preserve my life and all the meaning I’ve constructed for it?

There are many different kinds of life and the overwhelming conclusion of suffering people and those who care for them, is that it’s up to that person to decide how and what their life means, with the help of their family and community, and possibly the assistance of their physician. This right to autonomous decisions about your own life is not usually controversial. But what happens when a person cannot make those decisions for themselves? Almost universally, someone close to them steps in.

In the case of children, we rely on the parents to make decisions in their best interest and only in exceptional circumstances do we take that responsibility away. Many of the children I care for are pretty sick. They are often dependent not only on their mother or father or family but on whole teams of caregivers. Their lives often still have meaning. They can’t usually tell me that, but I see it in their eyes, in a reactive squeeze of a finger, or a laugh, or in their family’s devotion to caregiving. They have taught me the extremes that individuals and communities go to preserve and value all kinds of life. Many of these patients have also taught me the risk of blindly avoiding death. Something that prolongs a heartbeat or preserves the flesh does not always uphold life.

So who gets to decide what is right for a family or community or a life?

Sometimes it is clear, often it’s complicated. But I can tell you this, in all of my family meetings, in all of my discussions with dying patients, in all of my time caring for vulnerable children, during all of these lengthy, heavy, inspiring conversations about the meaning and value of life, no one has ever asked for the opinion of Samuel Alito. That’s because these are deeply personal questions about what it means to be alive. They’re questions we must answer for ourselves with whatever spirit moves us, whatever religion may guide us, whatever community supports us, and whatever world surrounds us.

I am pro-life. And it is because of that strong stance on life that I am also very much in favor of abortion access.

The core conflict in the disagreement around abortion is between the life and autonomy of a pregnant person and the real, potential, or imagined life of the fetus. You can view this conflict with many different lenses. You can view it philosophically, understanding it through personhood and rights and autonomy. You can choose to look at it from the perspective of public health, understanding it through the social impact and epidemiology of pregnancy. You can apply a religious lens, and address the conflict with passages from your holy book. You can resolve the conflict with political language, focusing on power or gender discrimination. You can focus on all of the medical indications for abortion and its central role in women’s health care. You can even try to use the United States Constitution to resolve the tension, ostensibly by reading through the lines, but perhaps just by waving it over your head while yelling.

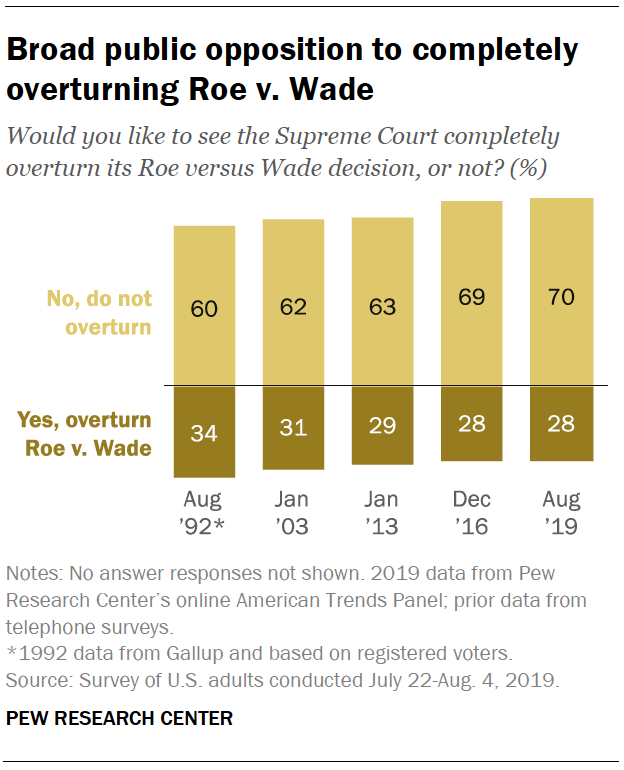

Choosing which lens to look through doesn’t seem to change our conclusions. Those appear to be informed by the spiritual, cultural, and lived background of the person looking through the lens. Our conclusions are often complicated or contradictory, at least partly because we all realize that each situation is different. This purple and green chart is a summary of several prominent polls that ask about abortion. Each asks the question differently, including slightly different caveats or exceptions. However, it is clear from these polls that an overwhelming majority of Americans do not think that abortion should be outright illegal. A gross majority of people also do not want to overturn Roe v. Wade.

However, if you dig further, people’s views are a little more unclear. For example, when a Vox poll asked follow up questions to the group of participants who thought abortion should only be legal in rare circumstances, they gave surprising answers. Over half were still against overturning Roe v. Wade, almost half of these folks felt that new restrictions were moving in the wrong direction, and a whopping 71% said they would give support to a close friend or family member who had an abortion — even though they had stated that abortion should only be legal in rare circumstances.

What am I getting at with this? Our views on this tangled, emotional, ancient, and vital question about life are just as varied, intricate, stirring, and important as the situations that force us to ask those questions. What does life mean to me? What does my life mean to me? Do I choose that aggressive cancer treatment even though it will make me sick? Do I leave my mother on the ventilator after her stroke? Do I carry this pregnancy to term? These are hard questions, which often feel impossible, usually do not have a right answer, and certainly do not have the same answer for everybody. They are questions best answered in discussions with family and community, in slow long walks in the woods, in peaceful, careful thought. We taint them when we have to answer them in the courtroom.

So how did we get here? Why is it like this? One compelling answer to that question involves a premeditated play for political power using the once nuanced and devout beliefs of evangelical Christians. Prior to 1979, most evangelicals felt abortion to be a Catholic issue and many of their theologians and followers felt there were many valid reasons to end a pregnancy, including individual health, family welfare, and social responsibility. Many folks were pleased with the 1973 ruling in Roe v. Wade and its affirmation of the separation of church and state. The change in 1979 was not a grassroots moral uprising 6 years after the supreme court ruling. It was a methodical mobilization of a religious group for political purposes, from the top down, by Paul Weyrich. The same Paul who famously said that he did not want everyone to vote because it increased his political power.

There is an even longer historical context, dating back to ancient times, and traced through the writings of various white men over the last several centuries, almost always driven by personal religious sentiment. Jill Lepore, a historian, provides a concise critique of the legal case presented in Samuel Alito’s leaked memo, what she called a “historically impoverished and bizarre analysis.”

“Alito, shocked—shocked—to discover so little in the law books of the eighteen-sixties guaranteeing a right to abortion, has missed the point: hardly anything in the law books of the eighteen-sixties guaranteed women anything. Because, usually, they still weren’t persons. Nor, for that matter, were fetuses.”

– Jill Lepore, for the New Yorker

The debate over how we arrived here is not especially prudent, even if it can remind us of historical inequities and highlight only recently sewn political divisions. An equally imprudent debate, over when life begins, also fails to help us reach a social consensus, unless that social consensus is that one cannot be reached. Biologists define life broadly, counting a capacity for growth, reproduction, and change before death. A giraffe is alive. A rock is not. Viruses are a classic test case, but most agree they are not in fact alive, mainly because they do not produce their own energy and require a host to propagate. So is a fetus most like a giraffe, a rock, or a virus? When does its life begin, separate from the life of its mother? At conception? Before? After the baby smiles and connects with the world? When primitive cardiac cells pulse on an ultrasound, totally dependent on the womb in which they exist? When someone starts to love the idea of a potential person joining their family? Who decides? There is no clear moral authority here.

The Catholic catechism (teachings of the Church as an institution and not holy scripture) that forbids abortion at any stage of the process rests heavily on a passage from Jeremiah (1:5). “Before I formed you in the womb, I knew you.” A Protestant follower of the Bible, who does not rely on the Pope and his clergy to interpret holy scripture for them, could easily interpret that to mean a free floating sperm, pre-womb energy, was in fact also a potential life worthy of protecting. Should states be able to outlaw masturbation because of this interpretation? How would they enforce that? Not all Christians may find that idea appealing.

There are also strong religious arguments that support a woman’s life and her ability to protect herself and her family. Specifically, many Jewish traditions clearly support a woman’s right to abortion “until the head emerges” if her life is in danger, likening it to self-defense. There are also passages in Exodus, a book shared by both Christians and Jews, which when properly translated, clearly value the potential life of the evolving fetus less than the life of the woman carrying it. You can find religious arguments for safe and legal abortion in some form from all major religions, including Islam and Hinduism. It all depends who is looking through the lens.

There is no clear moral authority on when life fully begins. It is a deeply personal sentiment, informed by someone’s spiritual proclivities, life experiences, community, and culture. The very first amendment to our constitution protects this freedom of religion. We do not collectively agree about when life fully begins. And in fact if you sit with this question long enough, savor it, feel around it with your fingers, it becomes clear that becoming a life is in fact a process and not a moment.

For our argument’s sake, let’s say life does begin at conception, or at least a few days after when there exists a clump of cells that we can call alive. This clump of cells cannot live without its mother host until it has incubated for roughly 23 weeks. Then it cannot live without millions of dollars and hundreds of staff in the neonatal intensive care unit. Then it once again cannot live without family or community to feed and care for it. After a few months it will start to smile. Another dozen months and it will start to walk and think and communicate in rudimentary ways. Another few years and it will start to have memories. After a decade of round the clock care, it will be functionally independent, though most would agree not fully neurocognitively developed until a full second decade later. When does vulnerability end? Surely some time before we start to try you for crimes as an adult. When does life start? When do we change from rock to virus to giraffe? I’m not sure, but it happens rather slowly, doesn’t it? I’m certainly not sure enough to make a firm law about it.

It becomes helpful here to set aside the theoretical and potential life of a fetus and turn to the real and full life of the woman in whom the fetus exists. The way you choose to balance these two interests is again entirely dependent on your values and beliefs, informed by your spiritual, religious, or moral background.

An argument for bodily autonomy is sometimes the only one people need to be convinced of the need for abortion access. I’ve seen comparisons made to the extreme protections for bodily autonomy in other areas of law or healthcare, like organ donation. Even after you’ve died, even to save a life, we are not allowed to violate your body and give away your organs. I find this line of reasoning interesting for two reasons. First, there is a small but important misunderstanding about the path to organ donation. Second, there is a small but vital bioethics distinction that waters down the analogy.

It is indeed true that we cannot take the organs of a dead or nearly dead person without their permission. However, as with every scenario we’ve discussed or imagined regarding the complexities of life, it is not that simple. A common situation we encounter in the hospital is that of a young person, tragically and fatally injured, who never thought about their impending death, let alone organ donation. In these cases, the patient’s family makes decisions for them, including about organ donation. Many families find consolation in their grief and meaning from tragedy by donating the organs of their loved ones to improve or save the lives of others. It’s tradition at our hospital to pause our work and line the hall between the intensive care unit and the operating room to pay tribute to the patient and their family and the complex community based decision making that lead to their difficult decision. We know how challenging it is to make these decisions, when your loved one cannot tell you what they want or need. Thankfully, most people deciding about abortion can make their own decisions about their own bodies.

Still, we need to honor the weighty difference between organ donation and abortion. Bioethics delineates between action and withholding. I encounter this discrepancy at work all of the time. There is a difference between choosing not to place someone on a ventilator and choosing to take someone off of the ventilator once they’re on it. There is a difference between withholding your organs even if they will save someone’s life and choosing to end a pregnancy. There is a difference, even though subtle, and we feel it, even if it’s inconvenient. Sometimes, not placing someone on the ventilator is the right thing to do for them. Sometimes, taking them off the ventilator is the right thing. This distinction helps patients, families, and their healthcare teams make safe, thoughtful, and careful decisions about what is best. Any person considering an abortion acutely understands the gravity of their act and their choice. We should respect and understand that too. Those same people are also the only ones to know the future or budding or full life that grows inside them. Line the halls and pay tribute to their difficult choice. You don’t know who that decision will save.

While there are legal precedents for bodily autonomy, there are strong cultural values that can distort or soften how we make choices for ourselves. I am sensitive to the pluralist argument and the appreciation that not every person or community values individualism above all else. I particularly enjoyed this quote from an anti-abortion activist in a New York Times Op-Ed: “We humans are not best understood as rights-bearing bundles of desires who progress through life by the sheer force of our autonomous wills. We are beings who are deeply dependent on one another — first and foremost for our very existence, as we did not come to be by an act of our own will…”

She is correct. We absolutely do not come into existence by an act of our own will, but in fact by a series of choices and circumstances by those around us, chiefly the person in whose womb we begin. It is by that person’s will, whether divinely or earthly given, that we exist. And it is this person best suited to balancing our conflicting values, needs, and priorities. Our life, our family, our community, our world. What a disregard for a mother’s labor, her time, her body, her essence, to treat her as merely a vessel with no soul or life of her own. Removing the choice from motherhood, to say that a woman must give birth against her will, removes the beauty of it. It desecrates the selfless act of love it takes to make a new life, and warps it into a miserable obligation. I know that my mother wanted me, gave up a little of her life and her soul for me. I have no doubt. Now, every child will wonder, did my Mommy want me or did Samuel Alito force her?

I am pro-life and so are you. It is clear to me from the nuanced and conflicting poll data that nobody thinks these are easy questions with easy answers. Anybody who asks you to call yourself just pro-life or just pro-choice probably has a political agenda. We all know it’s more complicated than that. We all want to make the right choice for ourselves, our families, and our communities. We all know that choice is not the same thing for each person or for each circumstance.

It is easy to get riled up about the things we care about. I do it all the time, I did it in this post. Samuel Alito has a lifetime appointment to an all powerful panel of judges that make decisions for us. He has not earned my empathy or patience. My fellow citizens, trying to make the world a more just and righteous place? They absolutely deserve my empathy and patience. Abortion is a personal, complex, and heavy part of our lives, which makes it a political tinderbox well suited to firing up crowds and making us vote. This system keeps us blissfully unaware until right before the polls open. Several surveys were conducted in the wake of the leaked supreme court opinion that asked participants about their knowledge of the current legal landscape surrounding abortion. In one poll of respondents in the 22 states that have passed abortion restrictions since 2020, only 30% were even aware of those restrictions. How can our politicians be acting in our best interest if 70% of us don’t know what they’re doing? How can they be carrying out our will if their decisions disregard the majority opinion of their constituencies? We are not as divided on this as we think we are. I am pro-life and so are you. The politicians trying to make this question seem easy? They’re pro-power.

The polls tell me that if we all truly voted our conscience, at least 70% of us would be voting for common sense regulations around abortion and certainly not voting to criminalize it. But we aren’t able to vote on this matter. Instead, we’ve been gerrymandered into a situation where 5 constitutional law professors have the power to decide what life is and what it means to us. And when they give up the ghost of Roe v. Wade in the next month or two, that spiritual decision about life and all its glory will be handed off to a group of state legislators who are not representative of the states they serve. Our state legislatures are overwhelmingly white, overwhelmingly male, and more importantly, overwhelmingly wealthy, with lived experiences and perspectives that are nothing like ours. I don’t want them in my ICU room after a car accident, telling my family what my life is supposed to mean. I don’t want them in my clinic, telling my patients how to make big choices about their mortality. And I don’t want them in my home, telling me what is best for me and my family. They’re pro-power. I’m pro-life and so are you.

I am one hundred percent, all-in, irrefutably in favor of life, its mystery, its beauty, its finiteness. It is because of this, not in spite of it, that I’m in favor of easy, safe, and legal abortion.

Very well elucidated, Dr. Twan! I am reminded of Molly Ivins’s writing on this, where she points out that not all fertilized eggs are successfully planted in the uterus. (I think the figure was perhaps four out of five.) A very small percentage of them are ectopic pregnancies, which can kill the mother unless aborted. And the rest are simply swept downstream at the next menstrual cycle… and, as Molly said, “We don’t give funerals for Kotex.” But maybe we’ll have to start.

LikeLike