“He was mortified. He couldn’t believe he had missed it.”

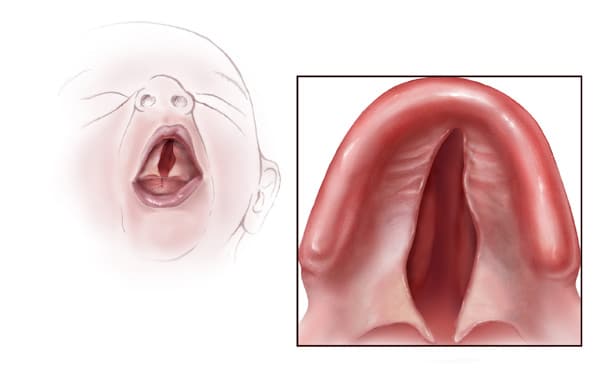

We had a new patient in the clinic, a 6-week-old healthy baby girl who had been struggling with feeding and latching. Her mother was not a new mother and had insisted over and over again to her pediatrician that something wasn’t right. On one occasion, she had even pointed out that the back of the baby’s throat looked wrong. The thing that hangs in the back looked like a whale tail. I’m not sure if her pediatrician actually looked at the baby’s uvula, but either way they missed the enormous cleft in her palate.

The pediatrician had seen cleft palates before, had even referred them to our clinic. It’s something you check for even when the parents don’t think anything is wrong. It’s definitely something you check for if your patient is having trouble with feeding. I can’t imagine not checking if your patient’s parent told you they saw a bifid uvula. But they didn’t find it. Not for six weeks. My boss was shocked. She assured me this was usually a very good pediatrician. I’m sure that was true. We could not imagine how it was missed. What was different about the patient? I entered the room and wondered if what I saw was the reason. The patient and her mother were Black.

I couldn’t even find a diagram of a cleft palate on a Black baby. All of the photos and illustrations were of white patients.

I remembered another mother-daughter patient dyad in medical school. A young teenager and her mother came to visit our 104-person lecture hall to tell my class about their experience with the daughter’s osteosarcoma. They talked about how hard it was to have cancer in your leg, especially as a high school athlete. They discussed the physical and emotional burdens of treatment. And they highlighted the power of support groups. But they also focused a lot on her delayed diagnosis. They told us they had to visit three different orthopedic surgeons before one of them took her pain seriously and ordered more tests. They told us that almost every doctor discounted their story and told them these were growing pains that would just get better on their own. They told us about the struggle, perseverance, and ferocity it took to make people believe them. This family was also Black.

In the almost hour-long session, my classmates and I asked a lot of questions, but none of us brought up race. Neither did the patient or her mother, seated across from a wall of mostly white medical students. I didn’t know what to say or how to bring it up. I tried later to discuss it with my classmates, how ludicrous it was that we didn’t use that case to discuss racial disparities in medicine. How disappointed I was in myself for not speaking up in that moment and inviting them to tell us more about their experiences. How sorry I was that we had missed out on such a learning opportunity.

In the clinic, four years later, I was not silent. When I stepped out of the patient room to present this patient to my boss, I addressed my observation directly. I did not know why this great pediatrician had missed this diagnosis. But this patient was black and most of our patients are not. The speech pathologist working with us nodded and my boss shook her head at the realization. We stood in silence for a few moments. I expressed my relief that although this patient’s care was delayed, there would be no long-term consequences. I expressed my concern that the pediatrician might not have examined their racial bias. And I expressed my often unnamed fear that I too am not examining my unconscious biases. After all, how can you know they are there if it is unconscious?

We will all claim that we treat all patients equally. That is our job and we have no intention of doing it any other way. But intention is not the same as outcomes. And it is very clear from our outcomes that our system is designed for white folks. White patients have better outcomes for cancer, heart disease, and kidney disease. White children have their appendicitis pain treated at a much lower threshold. White women are much less likely to die during childbirth. White folks are much less likely to die from COVID-19.

Some of this difference can be explained by socioeconomic factors, historical inequities, and system influences. A lot of the difference is attributable to personal interactions. Some of it is entirely unaccounted for. The disparity is from things like miscommunication, cultural mismatch, or misunderstood patient preferences. It’s from small, subtle, unconscious biases that add up to lower life expectancies. It’s from fast-paced, quick decisions based on gut instincts that have been cultivated in a system designed for straight white men. It’s from unintentionally minimizing a mother’s concerns and missing her daughter’s cleft palate or cancer. Nobody thinks it’s them, but it has to be someone.

I really don’t want it to be me.

There are a lot of suggestions on how to prevent this: recognizing and understanding our implicit biases, expanding our exposure to positive narratives and images of people who don’t look like us, and intentionally building partnerships with our patients. These are all designed to overcome the cognitive dissonance of our explicit desire to treat patients equally and the evidence that clearly demonstrates we are not. They are good suggestions, but they are insufficient.

Our goal cannot be to treat patients equally. We cannot treat all patients the same because all of our patients are not the same. Equal treatment is not equitable treatment. A Black woman with a history of abuse will need different care from her obstetrics team than the white woman with a birthing team in the room next door. She may need more time, more patience, and a trauma-informed approach. A homeless patient with an addiction and a neck abscess needs different care from his surgical team than the otherwise healthy lawyer with an abscess in the same spot. He may need different antibiotics, a different approach, or a different informed consent process for surgery. A young trans patient will need a different style of well-child visit than the cis and straight patient the pediatrician saw before them. They may need a longer visit, different safety questions, or more time alone with the provider.

If these folks received the same care as everyone else, we would fail them. If all patients received equal treatment, they would not get the treatment they need. If we tell ourselves that we treat all patients equally, we will not acknowledge or check our own biases and we will not address or treat the unique traumas and experiences of the patient in front of us. We will be mortified, time and time again, that we missed something or mistreated someone.

If instead, if we start to believe that we are capable of missing something, that we are capable of mistreating people, we may become more vigilant. We may resolve our cognitive dissonance and actually become the doctors we say we are, we pledged to be, we aim to become. If we strive to treat patients equitably — and not equally — we may pause more often, we may consider that we’ve been conditioned not to hear some patients as loudly as others, we may choose to listen more attentively to a mother’s concerns, and we may look one more time for a cleft palate. We may start to practice equity in an unequal world. Maybe it won’t be us.

Great analysis of an inadequately recognized problem.

LikeLike

Your post is a wonderful reminder of how the physician has to treat the whole patient, taking into account that person’s past history and the impact of their social status, race, and physical weaknesses on that history.

When I visited my doctor once, he was putting another doctor into his private practice. The second doctor saw the scar on my leg and took it as an ACL repair, even though it was in the wrong place for that. And this doctor never asked me what the history of the scar actually was. He just “knew.” That was when I went looking for another doctor.

Which brings me to another point you so eloquently made: the most important thing a doctor can do is listen. Instead of diagnosing off the cuff, find out what the patient is experiencing, because that person is trying to give you valuable information. That information came from somewhere, and even if it’s wrong or misleading, it’s a window into the patient’s life experiences.

LikeLike

Wonderful piece, Antoinette! Holds true for all professions.

LikeLike