No one taught me to be racist. They didn’t have to.

There was only one Black family in my neighborhood. The patriarch used to walk around the block every evening, just before dark, never after. I don’t even know his name. We just called him “walking man.” He always waved back. I never wondered why there was only one Black family in the neighborhood. No one ever asked me.

There were only a few Black kids in my elementary school. I was friends with one of them for a while. She came over to play at my house one time. When my Mom took her home, I asked why she lived in the trailer park. My Mom told me it wasn’t nice to ask questions like that.

In high school, we touched on slavery. They showed us the map of triangular trade, none too caught up by the fact that one of the routes traded people. We talked about how the Civil War was partly, maybe mostly, about states rights. We blew past Jim Crow, lynchings, J. Edgar Hoover, and discriminatory housing policies, since we had spent so much of the year on the 13 Colonies, the American Revolution, and manifest destiny that there wasn’t much time left.

I never questioned why there were only two Black students in my AP classes. No one ever asked me to. I never thought anything about how it might feel to be there, alone, surrounded by folks who never considered them for all that they were and all that they had done. There were no Black teammates on my swim team. I never had any Black children in the dozens of swim lessons that I taught. I never really wondered why. And no one ever asked me to think about it.

In college, I was lucky enough to encounter patient teachers and even more patient Black friends. They started asking me these questions. They let me muddle through answers. They gave me the space to stare dumbfounded at them as I discovered enormous gaps in my historical knowledge. I had scored perfectly on my AP US History exam. How could I not know this?

How could I not know that until the 1960s, the Federal Housing Administration refused to insure mortgages for Black families. In fact, they refused to insure white families who tried to buy houses in Black neighborhoods. Almost all of my family’s wealth was tied up in our home. My parents took loans against it and built equity without paying rent. More importantly, my immigrant grandparents did the same with their prized suburban homesteads, bought cheap after the war. My whole life was financed and built on a racist foundation. Of course there was only one Black family in my neighborhood. Of course my friend lived in a trailer park. Our government ensured they would be several generations behind me in the quest for financial stability and a steady home.

How could I not know that the FBI wiretapped Martin Luther King Jr.? How could I not know that they literally assassinated Civil Rights leaders? How was this not part of our contemporary history curriculum? Why was I so easily convinced that the Civil War was about state’s rights? Our history curriculums are at best irresponsible and at worst dangerous.

When I think back on these lessons, I am not sad or guilty. I am grateful for my mentors’ and colleagues’ patience. But I am mostly angry. The reason we learn history is to understand where we come from and how we got here, partly so that it “doesn’t repeat itself,” but also so that we can properly understand the problems of the present and effectively solve them. If we don’t know what we did wrong, how can we make right?

People love to claim that they don’t have a racist bone in their body. I do not care if you personally think you’re racist or not. It’s irrelevant. These things happened and we never reckoned with them. We never atoned for these sins. Every bone in my body was created in a house funded by a racist government that killed its opposition and tried to keep the truth out of our public schools. Every bone in my body inherited the unpaid debt accrued by millions of enslaved people whose bodies and labor and lives were stolen from them and pumped into our nation’s fledgling economy. Every bone in my body lives in a country that had to amend its founding document to remind ourselves that Black people are actually five fifths human and not three.

This is not my fault. I didn’t do this. I don’t need to feel guilty. Not yet. But if my bones rest, if they ignore their legacy, if they don’t try to make amends, then I am complicit. If I cover my ears and shake my head and try to ignore the onslaught of horrible news and terrible history, I am complicit. If I don’t challenge myself to think bigger, learn more, teach better, listen harder, and dig deeper, I am complicit. I don’t want to be complicit. I don’t want to feel guilty.

No one is asking us to feel guilty. They are just asking us not to be complicit. By not teaching us about systemic and explicit racism, by ignoring Black history and America’s many shames, by not asking us to think about the inequities around us, our teachers and communities failed us. They didn’t teach us to be racist, but they certainly didn’t teach us not to be.

Is it fair that we now have a responsibility to educate ourselves? No. Does it matter? No. This is where we are. We can only change where we are going. Read new things. Ask questions. Find some coworkers and start a committee to demand equitable hiring practices at your job. Be aware of yourself and what you say. Be willing to reflect and make mistakes and adjust. Be willing to spread the word to others. Be willing to pull up next to a Black person stopped by police to make sure everyone gets home safe. Fight for better curriculums. Fight for desegregation. Fight for the future.

You didn’t have a choice in the past. But you do now. Don’t make the wrong one.

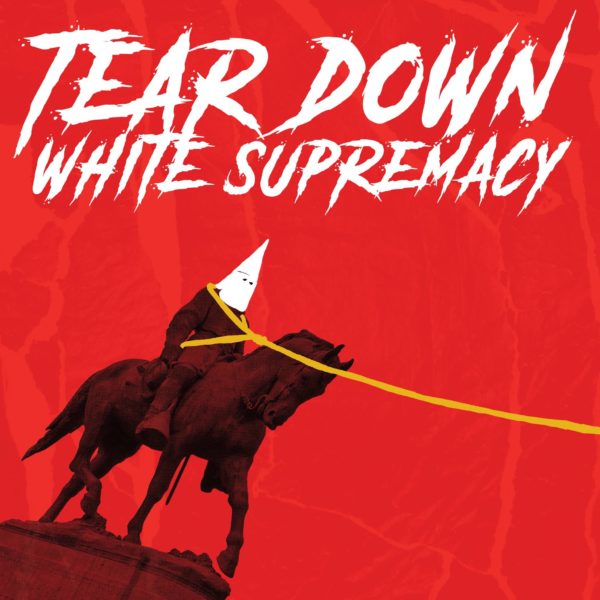

By Jesus Barraza and Melanie Cervantes from justseeds.org